From The Archives: The Many Holocausts

Three survivor writers had the power to speak and their readers the courage to listen.

This Holocaust Remembrance Day, commentated in the shadow of the largest single massacre of Jews since World War II, is especially unbearable. We must once again question the ability of words to convey the unspeakable and of the willingness of people to listen.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Atlantic.

The Many Holocausts

The Atlantic, January 26, 2020

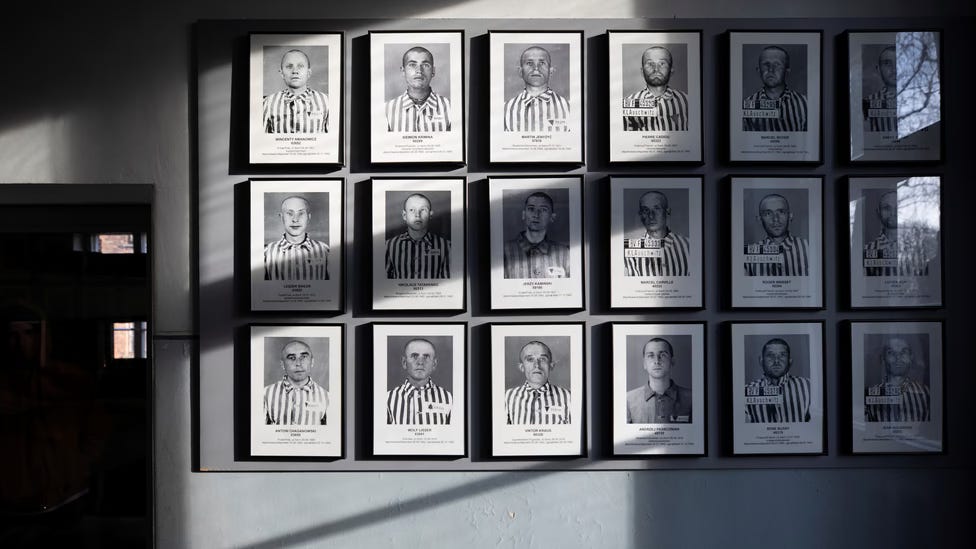

Almost inconceivably, the two most acclaimed Holocaust writers were imprisoned in the same Auschwitz sub-camp, Monowitz, at the same time. Some survivors even remembered them occupying the same block. There, they suffered the same unspeakable deprivations, the deadly cold, disease, hunger, and dehumanization. In that insanely polyglot place, they both learned the lifesaving lingua franca—German—and miraculously passed through selections. And even after liberation, when tens of thousands still died, they somehow endured.

Yet, despite all their shared horrors, Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi emerged with profoundly different versions of the Holocaust’s meaning and lessons. Their memoirs made them national icons, not only because of the compelling voices in which they were told, but even more so because of what their audiences were willing to hear.

Americans would not have listened to the enraged Wiesel who staggered out of Germany’s Buchenwald concentration camp, one of the relative few to have survived the agonizing march from Poland. In the first drafts of what would become his classic, Night, Wiesel expressed fury at the Germans, his family’s Christian neighbors, Jewish collaborators inside the camps, indifferent Jews overseas, and especially God. He described desperate sexual encounters among prisoners likely to die and the rape of German women by newly liberated survivors. Virtually all of this rawness was excised from La Nuit, first published in 1958, under the mentorship of the French Catholic humanist François Charles Mauriac. As noted by the critics Ruth Franklin, Ron Rosenbaum, and others, Mauriac condensed an embittered 865-page Yiddish manuscript into 254 pages of literary French all but drained of acrimony. The need for revenge was replaced by acceptance of the silent martyrdom traditionally preferred by the Church. Originally a cry of despair, the description of a Jewish boy’s hanging by the SS became, in Wiesel’s new homogenized version, a parable of saintly suffering.

Nevertheless, La Nuit could scarcely find a publisher, must less a wide readership. Nor was it an instant success in America, where the 1960 translation sold just 3,000 copies. Over the next 50 years, though, that number would soar exponentially, surpassing 6 million. Along the way, Night was selected by Oprah’s Book Club and spent 18 months at the top of the New York Times Best Seller List. Wiesel was awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Nobel Peace Prize. An entire generation of American high-school students learned about the Holocaust almost exclusively from Night.

That triumph owed as much to Wiesel as it did to his adopted country. In terms of Holocaust memory, the United States also evolved. During the 1950s and ’60s, the Final Solution was barely discussed, even among American Jews, and then mostly in whispers. The photographs taken at Buchenwald by my uncle Joe, a U.S. Army officer, were hidden in a cubby under our basement stairs. In five years of Hebrew school, I learned about the miracle of Israel but virtually nothing about the murder of a third of my people 20 years earlier. When, at age 15, I heard a lecture at the Jewish community center by a frail-looking writer named Elie Wiesel, I was shocked that someone would speak so publicly about Auschwitz.

The radical change came in the ’70s, after the Six-Day War gave American Jews the confidence to confront the Holocaust and after the Yom Kippur War dislodged Israel as the centerpiece of American Jewish identity. One result was the Soviet Jewry movement—spurred in part by Wiesel’s seminal book The Jews of Silence—but also by the emergence of Holocaust awareness. Lucy Davidovicz’s The War Against the Jews was published in 1975, followed by the widely popular TV miniseries Holocaust three years later, and President Jimmy Carter’s 1979 Commission on the Holocaust, chaired by Wiesel. Holocaust-studies programs proliferated, as did March of the Living–type pilgrimages to Poland. The process climaxed in 1993 with the opening of the $190 million United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, in Washington, D.C. “A museum is a place that should bring people together,” Wiesel declared, “not set people apart. People … should feel united in memory [and] bring the living and the dead together in a spirit of reconciliation.”

Reconciliation, rather than retribution, became the message that Wiesel and the museum he championed brought to Americans. “Even in darkness it is possible to create light and encourage compassion,” he wrote. “I still believe in man in spite of man.” Without conceding the uniquely Jewish nature of the Holocaust, and its centrality in his conflicted relationship with God, Wiesel told a different story to his countrymen. This was the hopeful theme of Schindler’s List and the many films and novels about Germans who opposed Nazism and about gentiles who saved Jews. It was evident in the purified diary of Anne Frank, whose “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are good at heart” anticipated Wiesel.

Could it have been otherwise? Would Oprah have interviewed a survivor who demanded the eye-for-an-eye execution of 6 million Germans? Would hundreds of thousands of American young people of all backgrounds pass through a memorial that taught “Never again” as a pledge to armed resistance rather than a plea for universal love?

Elie Wiesel understood that Americans could be educated about the Holocaust only in their own language: affecting and ultimately redemptive. That language had to include, as the memorial makes clear in the opening of its mission statement, “the Gypsies, the handicapped … Poles … homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Soviet prisoners of war and political dissidents,” who were also victims of the Holocaust. And that language could not be overly critical of America. Some scholars have alleged that the museum soft-pedaled President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s abandonment of the Jews and President Barack Obama’s refusal to intervene in Syria. At the Holocaust Memorial–sponsored rotunda ceremony I attended each year as Israel’s ambassador, congressional leaders and administration officials heard praise for the GIs who liberated Dachau, Buchenwald, and Bergen-Belsen, but scarcely a word about America’s refusal to admit Jewish refugees or bomb Auschwitz.

Wiesel raised no objection to this omission. His love for America—he carried his U.S. passport in his jacket every day—brought him influence among a succession of presidents and especially Obama, to whom Wiesel passed messages from the Israeli government. Universalism enabled him to speak out in favor of aid to the victims of other genocides, in Serbia, Rwanda, and Darfur, and to defend Israel in the face of mounting liberal criticism. Even when pressed into attending Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s controversial congressional speech against the Iran nuclear deal, Wiesel, already near death, received repeated bipartisan ovations.

That degree of celebrity would never be attained by Primo Levi, though he was arguably the finer writer. Like Wiesel, he became his society’s most revered bearer of Holocaust memory. Secular, humanistic, anti-religious, nonmilitant, and post-national, Levi spoke in a language intelligible to Europeans.

Nearly 10 years older than Wiesel at the time of his deportation, Levi belonged to a thoroughly assimilated family that thought of itself as Italian in a way that the Wiesels could never have been Romanian or Hungarian. Arrested as a partisan, he admitted he was Jewish only after concluding, naively, that it would ease his punishment. He was a brilliant chemist who viewed reality through a scientist’s lens, exacting and cold, so different from the young Wiesel’s spiritual, visceral world.

Though he was a prisoner of Auschwitz for three interminable months longer than Wiesel, was spared hard labor toward the end of the war thanks to his laboratory work, and managed to avoid the death march, Levi’s memoirs tell a story almost identical to Weisel’s. His observations, however, are radically different, as are his conclusions. Unlike Wiesel, Levi did not need a Mauriac to tenderize his prose. Tormented by the idea of killing even as a partisan, he refused to hate the Nazis. Indeed, his bitterest scorn was reserved for his bunk mate, Kuhn, who, after surviving a selection, prayed to God. “Kuhn is out of his senses,” Levi wrote. “If I was God, I would spit at Kuhn’s prayers.” Rather than dream of vengeance, he focused on observing, chronicling to the minutest detail, and commenting on ordinary people subjected to the most monstrous conditions. As his biographer, Carole Angier, concluded, “He did not just learn in order to survive. On the contrary; he survived in order to learn.”

Levi’s humanism appealed to postwar Europeans. Like Americans, their attitudes toward the Holocaust also evolved. Guilt, initially, was placed solely on the Nazis and assumed by West Germany, which alone paid reparations. Decades would pass before France (1995), the Netherlands (2000), Belgium (2007), and Austria (2018) officially assumed responsibility for facilitating the annihilation of Jews. Yet the insistence of historians such as Dieter Pohl, Götz Aly, and Dan Stone on calling the Holocaust a “European project” has yet to achieve widespread acceptance throughout the Continent. Culpability, rather, is ascribed to the virulent, provincial nationalism that the European Union was created to supplant. The EU institutions I frequently visited as part of Knesset delegations almost invariably featured exhibitions on the Holocaust and the fight against the fanatic patriotism that produced it.

Levi, too, tended to exonerate Europe. If This Is a Man, the original title of his classic Survival in Auschwitz, accentuated the personal, rather than the ethnic and religious, nature of the Holocaust’s victims and perpetrators. And if Wiesel never lost faith in humankind, Levi continued to believe in Europe, unreservedly returning to Italy after the war. His secularism also resonated with an EU that formally excluded Christianity as a source of European identity. This was the Europe that beatified the de-Judaized Anne Frank, and that praised The Pianist and Life Is Beautiful, both films about totally assimilated Jews who experienced no anti-Semitism before the Nazis. And Europe continues to resist viewing the Holocaust as an essentially Jewish trauma. Touring a French cathedral last summer, I was surprised to encounter not one but two Holocaust memorials, both to Jewish converts to Catholicism.

Levi’s darkness also resonated with those Europeans for whom an American-style redemption was too mawkish. Rather than subscribe to Wiesel’s “In darkness it is possible to create light,” Europeans preferred Paul Celan’s “Black milk of morning we drink you at dusktime,” and Irme Kertész’s Fatelessness and Kaddish for an Unborn Child. Like Kertész, Levi battled depression, and like Celan, he committed suicide. There is little light in Survival in Auschwitz, no more than in the most recent and successful European Holocaust films, Son of Saul and The Painted Bird. By contrast, an American film based on Levi’s work, The Grey Zone, proved too devastating for American viewers and failed at the box office. Levi’s willingness to criticize Israel and his commitment to rationalism, likening human types to elements on the periodic table, further endeared him to Europeans. That same exactitude dominates the Holocaust memorial in Berlin—geometrical, stony, and silent.

Still, Levi was not instantly celebrated in Europe. Begun in 1946 and published 10 years later, If This Is a Man sold only 1,600 copies. Though it gained in popularity in the 1960s, it was not until the ’70s, that transformative decade in Holocaust awareness, that Levi was able to quit his chemistry job and devote himself to writing. By the time of his death, in 1987, he was recognized as Europe’s Holocaust author par excellence, traveling to schools to talk about his Auschwitz experiences and speaking out against Holocaust deniers. His list of awards was long and, had he lived, would likely have included a Nobel Prize for literature. Instead, that honor went to Kertész, another dark, rationalistic, fiercely secular Jew who returned to his home country, Hungary, after the war, and later moved to Germany.

America and Europe incorporated Wiesel and Levi into their popular narratives. But who is their counterpart in the state that emerged in part as a reaction to the Holocaust, and was founded in significant part by its survivors? Which writer speaks of Auschwitz in a voice that Israelis are willing to hear?

The answer is virtually none. Israel is no country for the sentimental or the cerebral; Israelis would never have embraced a Wiesel or a Levi, or their sentient messages. Night was never a major best seller in Israel, and many of Levi’s writings were not even translated into Hebrew until after his death. And for good reason. Israelis saw the Holocaust as the inevitable outcome of 2,000 years of Jewish homelessness and Christian hate that was ended by independence and armed strength, rather than as a historical aberration to be denied recurrence by tolerance and peace. Nor do they believe that the existential threat ended with the liberation of the camps. For Israelis, it continued with enemy forces—not merely odious ideas—massed on Israel’s borders. More than a personal or human tragedy, the Final Solution was perceived in Israel as a national nightmare requiring a firm sovereign response.

That muscular view, coupled with the presence of hundreds of thousands of survivors, created a bifurcation in Israel’s Holocaust memory, a clash between Shoah—destruction—and T’Kumah, or rebirth. The schism was evident in the two main repositories of Holocaust memory: Yad Vashem, in Jerusalem, and the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, near Haifa; and in the name of the commemoration day, Yom Hashoah v’Gevurah (Holocaust and Heroism Day); and even in its date. Israel commemorates the Holocaust not on the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, but on the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. In the competition between mourning for the victims and lionizing the resisters, the latter clearly won, at least in the state’s early decades.

These were the years when native-born Israelis showed contempt for the millions supposedly slaughtered like sheep and the sabonim (“soaps”) who meekly escaped; when the exigencies of state-building justified the acceptance of the German reparations derided by many survivors as “blood money.” That environment, not surprisingly, produced poets like Abba Kovner and Uri Zvi Greenberg, who, despite their significant political differences, agreed on a militant rather than mournful response to the Holocaust. Novels and paintings, too, depicted the Holocaust, but preferred tales of resistance and fantasies of revenge to real-life descriptions of the camps.

But in Israel, as in Europe and the United States, views of the Holocaust evolved. The first milestone was the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann. Seen by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion as a platform for reminding the world about the Holocaust, the hearings also forced Israelis to confront their past. Especially poignant was the testimony of the writer Yehiel De-Nur—he used the pen name Ka-Tsetnik, “Concentration Camp Inmate”—who collapsed in the witness stand. But while he, like Levi and Wiesel, lived through Auschwitz, and wrote what he described as chronicles rather than literature, his books never achieved lasting influence. Quickly overshadowed by the Six-Day War and its heady aftermath, the trial might have faded into Israeli memory if not for the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which triggered a period of introspection throughout Israeli society, including its relationship with the Holocaust. The surprise Egyptian and Syrian attacks, which claimed 2,600 lives, proved that Israelis could also experience helplessness.

Like America and Europe, Israel began to engage the Holocaust in more nuanced and often agonized ways. Young Israeli writers, many of them native-born, began to imagine the experiences of those interned in the camps and even the Nazis who ran them. Dan Pagis, a poet and survivor, rose to prominence with his terse, tortured verse; David Grossman, whose See Under: Love explored the Holocaust from different dimensions, became Israel’s leading novelist. The process climaxed in the late 1980s with the trial in Israel of the former Sobibor guard John Demjanjuk. As during the Eichmann proceedings a quarter century before, survivors’ testimony forced Israelis to confront the Holocaust as an intensely personal, rather than national, memory. Demjanjuk’s release for lack of evidence only deepened the shock.

Those years saw the emergence of Israel’s preeminent Holocaust writer. Though not a survivor of the death camps, Aharon Appelfeld, a refugee from Ukrainian captivity who became a child cook in the Soviet army, nevertheless remained possessed by Holocaust themes. These included foreboding, loss, and above all the rootlessness of “a displaced writer of displaced fiction,” as Philip Roth described him. Appelfeld’s was a Holocaust of anger, and bore the mark of his determination to preserve its uniquely Jewish character. Attending a series of lectures he gave toward the end of his life, I was stunned by his bitterness toward younger Israeli authors who, he claimed, had abandoned their Jewish identity for secular Israeli culture, and whose Hebrew was shorn of Yiddish overtones.

Appelfeld’s rancor, his defense of Jewish heritage, and his refusal to extract universal or moralistic meaning from the Holocaust appealed to Israeli grit. Still, he would never attain Levi- or Wiesel-like stature. One reason is the immediacy of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which can eclipse the horrific events of 80 years ago. Grossman’s fame, like that of Amos Oz and A. B. Yehoshua, owed less to his treatment of the Holocaust than to his promotion of peace. Tension, meanwhile, continues to surround the lessons Israel should draw from the Holocaust—whether, as Netanyahu told gatherers at Yad Vashem, “the strong survive; the weak are erased,” or, as President Reuven Rivlin said at the same event, “the Holocaust will forever place the Jewish people as eternal prosecutors … against anti-Semitism, racism, and ultra-nationalism.”

Most striking of all, though, is the absence of a broad audience for any Holocaust book, even Appelfeld’s. In a country where Holocaust curricula are taught in most schools, where 18-year-olds ritually visit the camps before enlisting, and where the Knesset debates incessantly about expanding survivor pensions and extending them to the victims of fascism in North Africa and Iraq, how much awareness can any one writer add? Does Israel, where normal life comes to a complete halt on Holocaust Memorial Day, need another Night or Survival in Auschwitz?

The same cannot be said for Europe and the United States, where recent polls indicate an alarming decline of even basic Holocaust knowledge, especially among young people. Amid the passing of the World War II generation and the rise of extreme right-wing parties around the world, some with fascist pasts, the voices of Wiesel, Levi, and Appelfeld need to be heard more than ever. Now, though, they must speak in a unified language understandable to all audiences, American, European, and Israeli alike. And their message must be one—that the Holocaust teaches us multiple messages, all of them complementary. It is a message of hope, of humanism, and of Jewish national rebirth.

Obviously, according to Oren, the right is to be feared more than the left historically. No doubt that's true, but it is the historically tolerant left that is all about the dreaded nationalism now, as long as it is Palestinian. It seems that a rejection of religion is what is required, again, except for Islam. Yet Islam is the sole, remaining state religion exercised by brutal force. Why is that preferable? Hamas, is above all, about subjugation to power, including the Palestinian people and capitulation to it will bring freedom to no one, from the river to the sea. Or anywhere else.

There doesn't seem to be a rational foundation for deadly anti semitism throughout history except regarding a determined religious group that identifies itself, doggedly, as a birthright community. It will secularise, it will assimilate, but it will not forgo its exclusiveness. It will not totally bow down. That seems to be what ultimately makes it a target.

It stands in the way and it always has. It must yield. Or, else. Look no further than it's historical uniqueness, millennial survival, brilliance, pride. That's its sin. Long live Judaism, a beacon of inspiration and courage for all time. Reason has nothing to do with anti Judaism; human thirst for power, does.

I can't imagine writing about Holocaust authors and no mention of Viktor Frankl.