This is the final part of a three-part series on the dilemmas posed by Israel’s Iron Dome. Read Part I here and Part II here.

Throughout the opening decades of its existence, Israel’s defense strategy centered on the concept of hachra’ah—decisive victory. Whether striking preemptively or in response to an initial attack, Israeli forces would go on the offensive and take the battle deep into enemy territory. The principle reached its peak in the 1982 invasion of Lebanon and the siege of Beirut, but thereafter fell into disrepute. Israel subsequently engaged in an abortive war of attrition in Southern Lebanon, withdrawing under fire in 2000. Though Israel launched limited incursions into the West Bank (2002), Lebanon (2006), and Gaza (2008-9 and 2014), it generally adopted a defensive position on all its borders. The IDF replied forcibly to rocket and mortar fire, mostly from the air, but refrained from committing ground troops on a substantive scale.

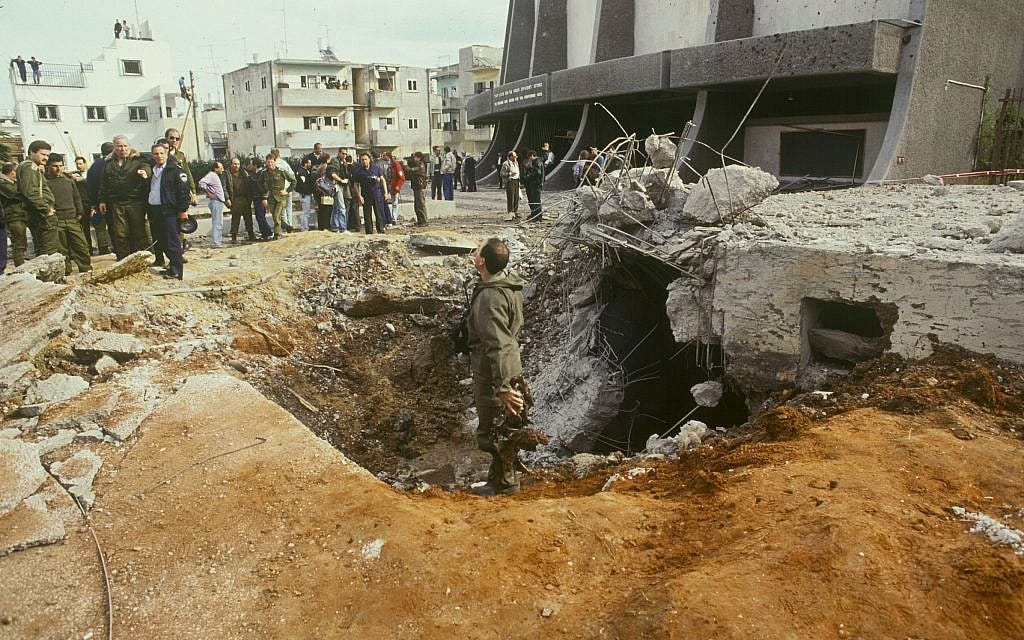

Previously, at least, defensive strategies had never been popular among IDF planners, nor did they prove successful. President Kennedy’s sale of Hawk missiles to Israel in the early 1960s was stridently opposed by many IDF leaders, among them IAF Commander (and future president) Ezer Weizman, who argued that defensive systems would deprive Israel of funding for offensive capabilities and weaken its resolve to attack. The so-called Bar-Lev line, built along the Suez Canal after the 1967 Six-Day War and designed to withstand Egyptian assault, proved tragically permeable in 1973. During the First Gulf War of 1991, Israel came under intense American pressure not to retaliate for the thirty-nine Scud missiles fired by Iraq, most at the Tel Aviv area. To assuage the Israelis, President H.W. Bush rushed Patriot anti-missile batteries to Tel Aviv. The Patriots managed to hit only one Scud, turning it into two, and our enemies learned they could bomb our major city with impunity.

Nevertheless, Israel went on the defensive toward both Hamas and Hezbollah. The cost of uprooting them, in terms of soldiers’ lives and loss to the economy, was deemed too prohibitive. American administrations, both Republican and Democratic, consistently opposed Israeli offensive action and Israeli leaders believed—tragically—that Hamas could be salved with Qatari cash. But the decisive factor in preserving the defensive position was the advent of a new anti-missile system.

Prior to October 7, Iron Dome intercepted more than 8,000 rockets. Had those barrages not been neutralized, and many hundreds of Israelis been killed, then the IDF would have forgotten about the costs and instantly gone on the offensive. Instead, Iron Dome played an instrumental role in enabling Israel to remain in a defensive posture. For a decade after the 2014 war with Hamas, Israel responded to the rocket fire solely with aerial, naval, and artillery bombing. Apart from Special Forces, no ground troops were committed. Ceasefires were eventually negotiated, Hamas was again paid off, and the status quo ante restored.

Or so it seemed. By recoiling from ground action, we now know, Israel enabled Hamas to build a massive military infrastructure both above and below ground. But that was just one impact of Iron Dome. The other was to deprive the IDF of the need to even think offensively.

Writing in the Times of Israel well before October 7, defense analyst Lazar Berman quoted a former brigadier general, Meir Finkel, who compared Iron Dome to France’s post-World War I Maginot Line. That monumental fortification absorbed a huge share of France’s defense budget, rendered its officer corps complacent, and gave the country a false sense of security. Invading France in 1940, the German army simply went around the line. “What was once a tactical defense mechanism to temporarily protect the civilian population,” Tel Aviv University political scientist Yoav Fromer, quoted by Berman, wrote, “has become a strategy unto itself.”

No more than the Maginot Line deterred the Germans, Iron Dome failed to convince the terrorists to abandon their rockets. On the contrary, even with its ninety-plus percent success rate, Iron Dome spurred Hamas and Hezbollah to greatly expand their rocket arsenal with the goal of overwhelming the system. And with one projectile in ten hitting its target, taking and disrupting Israeli life, rockets remained a key terrorist asset.

This reality has been painfully reaffirmed since October 7, with Hamas and Hezbollah firing some 19,000 rockets at Israel. The latter, with enhanced accuracy and often flat trajectories, has proven more capable of eluding Iron Dome. In a full-scale war with Hezbollah, with an estimated daily barrage of as many as 3,000 projectiles, all the Israeli systems combined—including David’s Sling, Arrow 2 and 3—will be incapable of protecting Israel’s skies. The country will have to call on the United States and its own advanced anti-missile capabilities (Aegis, THAAD) to assist in our defense.

Tactical, psychological, legal, and diplomatic—there are many shortcomings to Iron Dome, and yet clearly there is no alternative. The system still saves countless Israeli lives and provides time and space for the IDF to mount the ground action which, as the war in Gaza has demonstrated, is the only effective means of stopping rocket fire. That lesson will be more rapidly and massively applied in any future war with Hezbollah. The IDF will have to move swiftly into the two hundred Lebanese villages in which the terrorists have installed their launchers. Israeli troops will have to advance village by village, house by house, to end the incessant volleys. The cost will be incalculable.

Still, there may be one alternative. Several years ago, while serving in Knesset, I was approached by several longtime veterans of the IDF’s Research and Development Bureau. They complained about the army’s fixation on Iron Dome and claimed that system represented political and financial interests totally unrelated to national defense. Instead of investing in super-expensive batteries and interceptors that were still far from fool-proof, the veterans stressed, Israel could concentrate on laser technologies that were already within reach. Their pitch sounded to me a little like Star Wars and I wished them luck. After all, I, too, as the former ambassador who helped secure US funding for Iron Dome, was invested in Iron Dome.

I was wrong. The system, developed by Rafael and popularly known as Iron Beam (Magen Or, in Hebrew), is nearly ready for deployment. It focuses an extremely intense laser on the incoming projectile and literally cooks it. In its initial stage, at least, Iron Beam will work in tandem with Iron Dome which will still determine which rockets will or will not hit populated areas and can operate even in the bad weather that inhibits lasers. But at the cost of pennies per shot, Iron Beam will eliminate the terrorists’ ability to wage economic war against Israel, which previously had to shoot two $60,000 interceptors at each $100 rocket and enable the IDF to take down virtually anything aimed at us. Along with an airborne laser developed by Elbit, the new technology will render Israel all but invulnerable from the air.

Israeli leaders hope that Iron Beam can be deployed in time for a final showdown with Hezbollah. But even if it is, even if Israel is rendered completely immune to missile fire, we will remain vulnerable to terrorist attacks both across and under our borders. Our leaders will be criminalized by international courts and our products subjected to boycotts. And there exists the possibility that, as was the case with Iron Dome, Iron Beam will cause complacency in the IDF while our enemies devise entirely new ways to kill us. Israel will have to fight on multiple fronts, tactical as well as legal and diplomatic. The threats will remain diverse, concurrent, and potentially devastating. Each one will need its own Iron Beam.

You’re suggesting more “walking on egg shells” in Lebanese villages; gets lots of soldiers killled and achieves little. Sorry, but announce in Arabic that civilians have 24 hours to leave then you bomb them hard from the air, then send in the tanks. Giving civilians some warning is more than the subhumans in Lebanon and Gaza who indiscriminately target Israeli civilians. You also hit the capital, Beirut really hard.

The alternative is, you show weakness and the enemy wins. They’re already winning. Northern Israel is becoming uninhabited.

If Iron Beam proves effective, look to its being deployed by U.S. forces in Europe and the Pacific if not sold outright to specific NATO countries, Ukraine, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Japan and possibly Taiwan to name the most obvious candidates. As a collateral consequence, watch for a future pro-Israel tilt, even if only marginal, in these countries international proclamations.

Relatedly, when the current 10 year agreement negotiated under the Obama Administration is up, Israel might be able to renegotiate its terms from a position of strength (Iron Beam), if not scrap any future agreement altogether. If Iron Dome had circumscribed Israel’s military thinking, these 10 year agreements have limited Israel’s freedom of action on the battlefield.

I think Israel’s future also requires a publicly announced strategy that combines the defensive capabilities of its anti-missile defense with a clear line that any attack will be met with massive retaliation whose goal will be to prevent any future assault. Perhaps this element is left unspoken but implied, but the enemy leadership will be targeted from the outset - that way, if the enemy leaders goes into hiding or is on the move, this could be an early warning to Israel that something bad is in the works. In that region, a strong statement to this effect is the only form of deterrence worthy of the name.

But this needs to be combined with a plan to deepen Israel’s ongoing political integration into the region. Therefore, it should announce a plan for a future state of Palestine that is, however, conditioned on deradicalization, educational reform, transparency in a civil government and with a police force only (like Costa Rica). Gaza, once again, will be the test case but the disputed territories in Judea and Samaria can experiment as well. Jerusalem will not be divided but Muslim worship and their religious rights will continue to be respected, though all groups will have equal rights of access (in other words, the “status quo” that existed in the immediate aftermath of Israel’s liberation of “East” Jerusalem in 1967).

Of course, this will be a generational project so, in the near future, it’s not giving away much. Israel can always point to the allies’ treatment of postwar Germany and Japan as models but with a far smaller direct Israeli footprint. Such a political horizon should be enough to satisfy Saudi Arabia and the other countries that have decided their national interests require a rapprochement with Israel.

As a related matter, it would be helpful if Israel’s public diplomacy would at least take the time to mention that Israel in its modern incarnation was in part the result of an international consensus arising from the post-WWI territorial dispensation that also saw the creation of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Iraq and that the question, if any, should not be “why Israel?” but “while only Israel?” - in other words, why were the Jewish people the only indigenous group to be given the right to self-determination among all of the region’s indigenous groups? That reframing of the issue would serve as a counterweight to the current attempts at delegitimizing Israel through the lazy faculty-lounge theorizing on decolonization and settler-colonialism. At a minimum, as the saying goes, it couldn’t hurt.